|

|||||||||||

| Recent Projects | |||||||||||

| Kali-Kalisu: Phase II | |||||||||||

| The second phase of Kali-Kalisu: IFA’s initiative towards incorporating the arts in education by training schoolteachers across rural Karnataka started this June at Nrityagram with a series of intensive Master Resource Person (MRP) training workshops. Conducted in partnership with the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan, Bangalore, there were thirty-five beneficiaries of the training, of which twenty-five were government schoolteacher participants from last year (Phase I) and the remaining ten were freelance arts education activists. The workshops lasted two weeks and explored the many ways in which arts practices can be used by teachers to teach not just the arts but other subjects as well, and in doing so, use creative teaching methods that go beyond the textbook. Thirteen organisations and five independent artists facilitated the training programme, which gathered teachers from eleven districts. |

|

||||||||||

The first phase of Kali-Kalisu was a series of twenty hands-on experiential workshops conducted in seven districts of Karnataka, providing educators a chance to explore creative tools and arts-based approaches in their everyday teaching experience. About 500 teachers benefited from these workshops, which offered participants personal and professional development through exposure to a wide sweep of cultural knowledge, including music, dance, puppetry, theatre and the visual arts. Following these workshops teachers took their new-found knowledge into their day-to-day classes, enriching the learning experience in many schools across the state. Many teachers who were present at the MRP workshops acknowledged how participation in Phase I of Kali-Kalisu had improved their teaching methods and boosted their motivation. The second phase of the project aims to consolidate the work achieved in the first year and extend training to a larger teaching community, creating a network of teachers who share an interest in the arts and are eager to take such an initiative further. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| New Grant | |||||||||||

Under our Special Grants programme, IFA will be supporting and administering a community initiative of the Mir musicians of Rajasthan. Shrinking patronage, dwindling performance opportunities and migration of young artists to urban areas in search of other means of livelihood have had an unfavourable impact on the music of the Mirs. This project brings together the Mir singers and their patrons in an attempt to strengthen their shared sense of responsibility about their rich musical heritage. It aims to consolidate their musical repertoire and create cultural hubs and performance opportunities within the context of the artist. Through August and September, ten senior musicians will train sixteen boys in singing kafis, kalams, bhajans and banis and also in performing the Jhumar dance. Training camps will be held across three villages about 100 km northwest of Bikaner. The project will culminate in a two-day Mir musicians’ conference scheduled for the last week of October.

|

|||||||||||

| In The Public Eye | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Broken Images |

|||||||||||

|

Shabana Azmi performed in Girish Karnad’s Broken Images in Bangalore on 4 June 2010. Directed by Alyque Padamsee, the performance was a fundraiser for IFA. The play uses technology to create a one-woman psychological thriller involving the actress, who goes to pieces when confronted by her own ‘image’ about her life and identity. Performed at Chowdiah Memorial Hall, the play drew a packed house. It was a memorable evening, with actors Arundhati Nag and Arundhati Raja, who have played the role of the protagonist in past productions, being invited to join Azmi on-stage after a standing ovation at the end of the performance. One lucky member of the audience also won a round-trip to Dubai, sponsored by Kingfisher Airlines, our travel partners for this event. DNA did an interview with Azmi and Padamsee about the play which you can read here. | ||||||||||

Gati Summer Residency |

|||||||||||

The second session of Gati Summer Residency concluded on 9 July 2010 with an event titled ALL WARMED UP at the Sri Ram Center in New Delhi, which included performances conceived by the four mentored choreographers in residence this year. This year produced four exciting and cutting-edge performances: In the Light of Irom Sharmila by Rajyashree Ramamurthy, Impermanence by Shilpika Bordoloi, Rememory by Lokesh Bharadwaj, and Don’t be Dotty by Divya Vibha Sharma. Maya Rao, David Zambrano, Amitesh Grover, Jonathan O’Hear and Anusha Lall were the mentors this year. Click here to learn more about the performance and find out more about the residency here.

|

|||||||||||

| Announcement | |||||||||||

|

The third session of Bengaluru Artist Residency One, supported by the IFA under our Extending Arts Practice programme, is currently underway, with four young artists from around the country spending the next three months in Bangalore. Budhaditya Chattopadhyay, a sound artist from Kolkata; L. N. Bhuvaneshwari, a printmaker from Andhra Pradesh; Siddharth Karrarwal, a sculptor from Baroda; and Himali Singh Soin, a poet/art writer from Delhi, are the four BAR1 artists-in-residence for 2010. The artists will be presenting their work in the upcoming months, about which we will keep you posted! To find out more about BAR1, click here. |

||||||||||

The Association for Academics, Artists and Citizens for University Autonomy (ACUA), Vadodara—the nodal centre for curatorial theory under IFA’s Curatorship Programme—have organised a series of travelling workshops across India that address curatorial practices, titled “Curating Indian Visual Culture: Theory and Practice”. The first in the series of these research-based workshops is scheduled from 13–18 September 2010, for which applications will be accepted till 5 August 2010. Resource persons for the workshops include an array of artists and critics from India and abroad. Please click here to find out more about these workshops or visit our website for the application. The Katha Centre for Film Studies, which is the nodal centre for film curatorial practices under IFA’s Curatorship Programme, will conduct a three day workshop on Film Curatorial Practices from 12–14 August 2010. The workshops will focus on history of film criticism and curation, curatorial writing and research methods, context-specific curation, and more. At the end of the workshop, five selected participants will have the opportunity to curate a five-day film festival. Visit our website to find out more about the workshops and how you can apply. Under IFA’s Curatorship Programme, KHOJ, New Delhi, the nodal centre for visual art curatorial practice, will sponsor a two-month Curatorial Residency. This residency aims to build a practice-based training for curators and will provide the residents with the support of a network of practitioners associated with KHOJ, allowing the emerging curators to engage with various modes of artistic practice and critical writing. Geetanjali Dang and Oindrilla Mitra are the two emerging curators who have been selected as the first participants of this residency, which began this July. |

|||||||||||

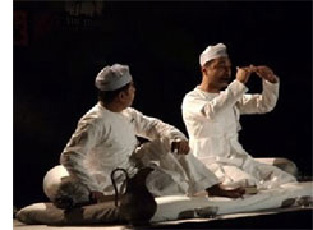

| Mahmood Farooqui, a grantee under our Extending Arts Practice programme, will present his work on Dastangoi, a sixteenth century performing art form of storytelling in Urdu. The performance is scheduled for 25 September 2010 at the Chowdiah Memorial Hall and incorporates multiple actors and styles to create a unique new take on the dastans or stories that revolve around war, romance, mythology and magic. The group also runs a very informative blog about Dastangoi. Tickets for the performance will go on sale in late August. |

|

||||||||||

| Slant, Stance | |||||||||||

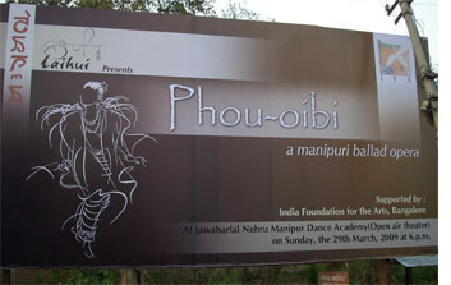

You are a traditional pena player and a person deeply interested in the rituals of Manipur, with an experimental approach to your work as well, in which you often blend innovation with the traditional, particularly in the project you worked on most recently under IFA’s support. How did this particular performance evolve? At the time I applied for the IFA New Performance grant, I was working in traditional ballad forms of Manipur. I was planning to fuse the Manipuri Ballad with Manipuri Opera. I was also working with Opera singers in Manipur and visual artists. I wanted the upcoming performance to break out of the traditional mode. Incorporating a strong supporting visual component would be one of the ways I would bring new elements into the performance. For example, I wanted the sets to be not mere props but function as an installation that would create an environment in which the ritual could be experienced as a performance piece. The performance itself draws from the ancient Manipuri ballad of Phou-Oibi, the Manipuri Goddess of rice-paddy, and is based on her mythological story, of how her influence reaches across the state and how she brings about good harvest. Though it is rooted in rituals, we wanted to present it as a performance per se in a theatre or stage, which would push it out of its “traditional” form (when it is performed in fields or shrines) and into more public spheres. The idea was to challenge notions of performance in Manipur and create a new language You’ve had diverse creative projects to your credit and you have worked in various capacities with individuals and organisations, mostly with the pena. Now with Phou-Oibi, you try to go beyond the pena. How do you trace your movement from the traditional towards the experimental?

The more involved I was in contemporary dance/performance, the more I wanted to explore my tradition and extend it, drawing from the rich resource of stories and forms of storytelling I had been exposed to as a child in Manipur, to create a new medium for performance. In my childhood I had seen performances of folk and legendary stories which, though ritualistic, were also entertaining. They were stories about reincarnation or star-crossed lovers, and something within me wanted to recreate them as performing art. My collaborations have been a big influence on me in this regard. When I was working with Yoshiko Chuma and the School of Hard Knocks, I was deeply influenced by her practice. I saw how fusing tradition and experimentation can create complex art forms. Performing with her was a great learning experience. In a way, I am neither comfortable with traditional forms of performance nor with contemporary performance. The former is not my way of functioning, and so much of the latter seems to shut people off by avoiding any obvious meaning. So more and more now I find my traditional training and roots helpful in experimenting within my own practice, be it in performance or music. In a way, a lot of my work is trying to straddle that ground between tradition and innovation and trying to create a middle way. What were some of your ideas which you incorporated into the performance of Phou-Oibi that you thought that were crucial to its “making new” of the ritual/traditional performance? In this effort, the music, sets and actors all played a big part in breaking the mould of the conventional ritual performance, which I was never comfortable working, anyways. Like I have mentioned above, we wanted the sets to be an installation. This supporting visual material, along with the lights and music, created the environment we tried to achieve, and helped us accentuate details of the narrative. Of course, the ritual performances do not have the stage lighting that we used to create an ambience and underscore shifts in the narrative. Similarly, with the music, we incorporated other instruments and several kinds of musical styles by orchestrating the pena with the vocal and rhythmic expressions of Moirang Sai, Moirang Parva, Sankirtana, Wari Liba and Lai Haraoba because we found that using only the pena was very limiting to the narrative. Likewise, opposed to the framework of the ritual in which only one person would enact the part of Phou-Oibi, we had multiple actors perform the same parts. On the other hand, it was interesting to me that the rituals had no rigid parameters for whether a male or a female shaman, priest or priestess should conduct them, and so we used this ambiguity to our advantage, creating a cacophony of characters and voices. Tell us a little bit more about your artists. How do you select them and how are they trained for the performance? The artists who participated in this performance are not just actors—they are complete performers who sing, act and dance. They are traditional dancers and musicians who we train in various exercises for about six months before the performance. They are not real actors because in a way they lack expression. We don’t train them in expressing themselves as performers in theatre. To me, it was more important that through their actions onstage—not through facial expression—the actors evoke the spirit of the rituals. So the actors were trained in ways that would help them physically manifest the grace and spirituality of the rituals and create that aura or energy even in a stage or a professional venue. They were allowed to meet the priests and priestesses who conduct the rituals; they were asked to chant the hymns and songs that are used in the rituals and of course there was much conversation and exchange about the rituals themselves.

How does the space that you inhabit—the geographical space that you call home—influence your work? Do you find it limiting to be working in relative isolation? In such a case, what does it mean to be able to perform in a cosmopolitan city? Though I live in Manipur, which is fairly isolated from a mainstream performance scene, I have performed internationally in Osaka, Tokyo, Singapore and New York and throughout India because of the many other performances and organisations I’ve been involved in. Of course, Manipur has a strong influence on my work, since my actors, instruments, and performances are all based in its rich culture. However, to represent the contemporary state of affairs in Manipur, one would think I would be obliged to address the political scenario of this part of the country. But I am not interested in politics that way. My work is an aesthetic exploration through a spiritual medium. Or rather, through my work I try to create that medium in which all these aspects can co-exist. As experimenting with traditional forms extends them into the contemporary, performing in a cosmopolitan or international city is like extending the origins and the reach of the rituals. Performing in other cities is not only an opportunity for me to present the work we do to a larger audience; it also helps me rethink my own performances and ways in which they can change over time, according to the audience. Do your performances change from venue to venue? Is what you are showing now a form of the play that has been finalised, or is it a constantly evolving process? Yes, my production’s performances do change from venue to venue, and no performance of mine is ever finalised, because I like to think of the creative process as constantly evolving. The venue matters little to me; in a way, it adds to the challenge of recreating the energy of the rituals, irrespective of whether we are performing at a royal courtyard, in an auditorium or a field. Depending on the venue, I maneuver the use of supporting visual material, installations, lighting and music to our advantage. Language, however, is the biggest challenge when performing outside Manipur. We must keep in mind that what we communicate through actions on stage becomes more important to the narrative than what is sung or spoken, and in that case everything else takes on a heightened importance. For the upcoming performance of Phou-Oibi in Kolkata, the performance will change in that there will be more focus on physical movement, rhythmic juxtapositions and visual atmosphere, through which we will try to make the narrative as comprehensible as possible. I believe the sound of what we say rather than the meaning becomes more important because sound or rhythm can act as a common language. My work is always trying to find that median between ritual and performance, traditional and contemporary, music/dance and language. My primary concern is to create a medium or environment in which the audience can feel what we perform, really experience its energy, rather than just be witnesses. What will you be working on next? Currently, I am working on orchestrating a musical composition with seventy-five drummers from across the country, to be performed in New Delhi on 18 September 2010 at Purana Qila. This performance has been organised in collaboration with the UN Systems in India, as a part of Stand Up and Take Action 2010, and as a call to end poverty now. And then of course there is the version of Phou-Oibi I am developing for the upcoming New Performance Festival, which I am excited to present to the audience in Kolkata. |

|||||||||||

---------------------------------------------- |

|||||||||||

Please do send us your feedback and response at biswamit@indiaifa.org with "Feedback" in the subject line. |

|||||||||||